The New Politics 1: Reality Entertainment

What a candidate for the US Congress and contestants from reality TV taught me about why Brexit and Trump happened

What a candidate for the US Congress and contestants from reality TV taught me about why Brexit and Trump happened

I was lost in my own thoughts, sipping a cocktail, when a striking thirty-something woman asked if she could take the stool next to mine.

The bar ran along in front of the kitchen in a trendy restaurant called Bracero in the Little Italy district of San Diego. It’s a district where a largely liberal population coexists with military staff from an enormous naval base, creating an interesting dynamic, and making it a key political swing district.

In front of me, bartenders mixed and shook and poured. The open kitchen, down to the left, was intense with chefs conjuring over the iron and flame. Behind me, in the dining room, staff in deep-blue aprons and flat caps bustled among packed tables, washed in the cacophony of a fashionable eatery.

I gestured for the woman, and her two friends hovering behind her, to go ahead and take the stools to my left, and returned to studying the menu.

After a few moments of chatter amongst themselves, the woman swivelled round on the stool to face me. “Any cocktails you recommend?”

“I’m afraid my knowledge extends only to this one.” I raised my glass.

“Which is that?”

I pointed to the eloquent description on the cocktail list.

“Something with Ancho Reyes,” I said, adding: “I have no idea what Ancho Reyes is.”

“Looks amazing. Is it good?”

I nodded, “Very refreshing.” I gave her the chance to break away and back to her friends.

“Could I taste?” She asked.

I was a little surprised, but then Americans are more forward, aren’t they? I pushed the glass along the bar towards her.

So began an evening’s conversation in which she turned to chat with her friends from time to time, but kept turning back to chat to me, and we exchanged tastes of different cocktails. I’d been looking for an evening of solitude after days of being sociable, but she was interesting, so I didn’t mind too much. I’ve also been around the block enough not to get taken in— although she came across as flirtatious, she wasn’t actually interested in me, I was just the nearest stranger to win over.

After a while she asked where my accent was from and said she’d guessed I was from abroad as I didn’t recognise her.

“Should I?” I asked.

“I was on The Bachelor. You know it? It’s a big reality TV show here. I get recognised all the time…”

My memory takes me back some years, and I’m eating a home-cooked dinner at the house of a friend.

She’s telling me about her experience as a contestant on a UK reality programme called Come Dine With Me, recorded a couple of weeks before. I tell her I don’t like the way these shows turn people into caricatures, and deliberately pick people who are going to clash with each other.

“Well that’s just the format. People want to watch for the drama in just the same way as a soap opera.” And as she explains more it becomes clear that there needs to be a storyline in each episode, secrets to discover, with goodies we cheer for and baddies we hiss. They cast people into roles, record a lot of material and then edit down so people fit the roles and the storyline.

So wasn’t she worried about how they would portray her?

“If you know what they’re going to do — and they all have roughly the same formula — you can take charge. You give them the caricature on a plate, and the juicy storyline. I knew the game from working in telly before.”

It appears that there’s a range of character types — just think of your average soap opera — and they’re looking for people to play them. And just like the soaps, clever or nice people aren’t seen as interesting. People want the juicy stuff to gossip about: the uptight one, the bossy one, the stupid one, the stroppy one, the lying one, the cheat, the stupid one. Characters to get angry about or laugh at. Those are the interesting characters, in soaps and on reality TV.

“I made out to be the ‘man-eater’ type. Then, because I focused just on that in the audition rather than trying to be nice and fun and so on that everyone does, I got picked because I was a simpler, better defined character.”

Why do people want to go into these reality shows in the first place, I asked?

“It gets them noticed, and if they get noticed enough they can use it as a springboard to other things.”

I guess that’s shown by Masterchef winners who get finance to open their own restaurant and then enthusiastic marketing from their local press, or Apprentice winners who get a deal to write a business book and lots of lucrative bookings to speak at conferences.

Personal progress has always been helped by who you know — but how much more powerful is it to have millions who know you? Being a character on reality TV that the press spills ink over, and people talk about, is a fast track to that.

Getting written and talked about, however, requires being gossip-worthy. That’s not about being nice or smart, it’s about being shocking, scandalous or even sociopathic.

Infamy is a magnitude bigger than fame in the ‘reality’ world.

I return to the present with the woman sitting next to me in the San Diego restaurant, and I ask what she’s doing now, following her Reality TV fame.

“I’m running for Congress.”

It takes a beat, but I realised that she’s not kidding.

The district I’m in currently has a Democratic representative, so if she’s not already the incumbent, she must be a Republican.

“So you might be running on a ticket with Trump?” I ask.

“Well he’s not going to win the nomination.”

“But if he does?”

“He doesn’t play well round here, so my position is: he’s not my choice but I’ll work with whoever is president. And it’s better to have a Republican congresswoman than a Democratic one under him because a Democrat won’t be able to get anything done. Everything will get blocked, the district won’t have a voice.”

I didn’t want to get too much into discussing right-wing politics on what I’d planned as a quiet relaxing night, so I steered the conversation elsewhere. But at the end, as she and her friends left, she gave me her name and told me to look her up online.

Of course, Trump went on to win the nomination and eventually the presidency, as he turned the role into a kind of political ‘Apprentice’, I remembered about this other reality-tv-star-turned politician — and I did put her name into Google.

It turned out that there were a number of interesting plot twists to her political story.

In the same way that Trump claimed to be a successful businessman but refused to release tax returns to support the claim (amid growing evidence that his money is in fact from debt), this Congress hopeful also claimed business success, but failed to file a required ethics report on time, including financial declarations, and then failed to complete it accurately.

It seems she first got involved in politics during an unpaid internship for George W. Bush’s presidential campaign for the 2000 election.

But right from the start of her political career, the facts seem to have been a little muddy. She got the internship job because she passed as Hispanic (although her mother is Chinese, father Canadian), and the Republican party desperately wanted to build some support in the Hispanic community. So they brought her in to ‘look ethnic’ and front up their campaign.

In speeches she even seemed to boast of her enterprise in getting ahead in this way: “I’m just ambiguously ethnic enough to pass for almost anything, and as a result ended up as a Hispanic coalitions coordinator,” she said in one.

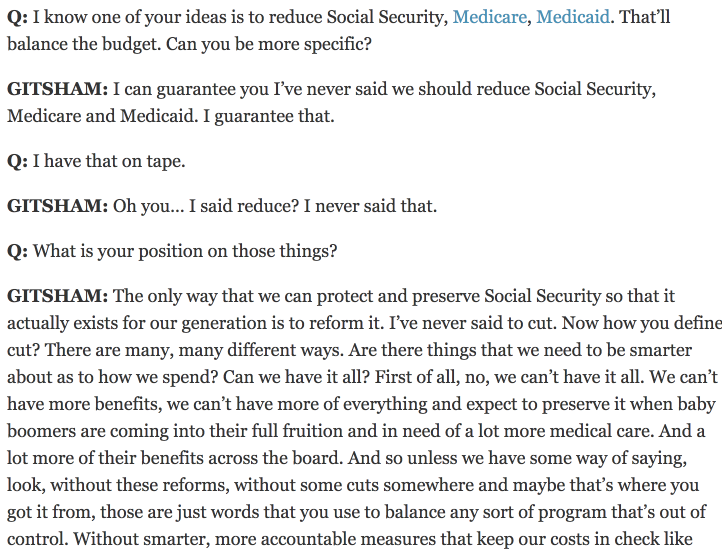

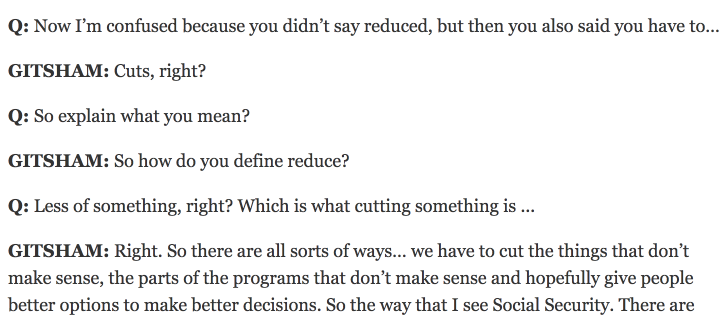

To get nominated, it seemed that she had to tread a very careful balancing act between saying what her Republican core wanted to hear, and saying what swing voters in the district could support. It led to some tricky interviews:

The same lack of public clarity, or sleight of hand, in discussing beliefs, policies and even definitions of simple terms also characterised the Trump campaign.

Both in this local campaign and nationally the approach seemed to be to make noise and get a lot of coverage, generating a lot of emotional reaction — but leaving people a bit confused about facts.

So what leads this kind of ‘reality’ politics to play so well in the news these days?

Back at the turn of the millennium I was a young journalist at the BBC. Someone high up had commissioned market research about why the typical audience for BBC News was mostly old rather than young, mostly male rather than female, and mostly ABC1 rather than C2DE in social group. The BBC’s management wanted, quite rightly, to appeal to a more diverse audience.

Sadly, the researchers came back with what I thought was a simplistic and patronising report. The BBC approach to news was, it said, to report the facts in a sober and balanced way that was respected by the current audience, but deemed as boring by the target audience. The desired target audience wanted to hear or read about things that gave them an emotional reaction. What did they need to worry about? What should they be angry about? What human story could they feel empathetically about? And what could they laugh about? News needed to be entertaining as well as informative.

To get this, they were consuming their news from the tabloids and independent radio. This was a diet of health shock stories (The Daily Mail in particular is sure to run one of these most days), celebrity driven stories, tear-jerking accounts of tragedy, a stream of bile at politics and other selected issues, and funny stories.

But the management took these findings at simplistic face value and reporters were encouraged to make news more entertaining, and to look for the emotional angle in stories as well as the facts. They also began to recruit many more reporters from newspapers, including tabloids, who they believed would understand this approach instinctively.

It slowly seeped into the culture of our media that an emotional angle would get a story on air, and placed well. In the immediate aftermath of an event, the focus of a report would once have been to establish what happened and what that meant. Now, one of the first questions is always ‘How do you feel?’

In the pressure to find the emotional angle, the news became less Kate Adie in style, and more like a Damian Day report from Drop The Dead Donkey…

In political reporting, coverage became much less about the policies, issues or debate, but about the fight between the individuals involved.

In the same way that reality TV editors and writers (yes, there are writers in ‘reality’ TV) select from footage to support a caricature, the journalists have ended up with a (mostly unconscious) filter for the characters and roles in any story. This one’s the roguish buffoon, this one’s the man of the people, this one’s the crazy leftie, and so on. Things these people did or said that supported the character they’d been cast as got into the news, things that didn’t stayed on the cutting room floor. Really, read some of the full text of speeches from source and then look for the clips that get selected for the bulletins or articles.

That led to the development of personality cults in party politics, as those who could play up to their caricature in pithy soundbites would get more airtime or column inches. And that led us even further down the wrong path.

Added to this was the increased time pressure on reporters — with cutbacks, increased output and the fight to beat competitors. That lead to a vulnerability to accept spoon-fed stories that were ready packaged up by spin doctors and PRs in an easily-digestible way with all the right emotional elements.

But it wasn’t just the BBC moving in this direction, all the media outlets were doing the same research, drawing the same conclusions, and making the same decisions.

From my perspective, it also seemed the BBC felt a little unsteady on its feet in this emotional world, so tended to take the lead from the papers. This became especially true after it had it’s wings severely clipped by Blair and Campbell over the ‘sexed up’ Iraq weapons of mass destruction dossier. Rather than setting the agenda, too many morning news meetings would look at the front pages of the papers to lead their debate of the agenda for the day.

And so the offering available from the news media homogenised around news-as-entertainment.

All of this has only amplified as competition in news media has increased, especially in the internet age. To get the audience you have to be the most entertaining, with the stories people can react to with the most intense emotions — and therefore share the most with their friends.

The bulletins and papers have now become: here’s the story to be angry about, here’s the story to be upset about, here’s the story you won’t believe, and finally here’s the one to laugh about.

And so it seems to me that political news has become the ultimate reality entertainment show. Who gets voted in or out this week? Who’s fighting whom? What’s the scandal and intrigue of the week? Who’s the baddie, who’s the goodie? Who’s the underdog?

The news therefore doesn’t now report what is real, but instead reflects a constructed ‘reality’.

And I think it’s this change in our news coverage that has actively led to the same ‘reality’ style in our political culture.

The politicians who get ahead are the ones who can play the reality news game.

In the UK, Nigel Farage is the master of this game. He knows the ‘character’ he has to play, does it well, and the reality news shows lap up the material he provides for each episode. Here he is red-faced and angrily criticising some undefined ‘establishment’ on some issue or other (where we’re not quite clear on the facts, but never mind) — and aha, here he is laughing heartily with a good old British pint in a good old British pub, so he’s clearly a man of the people. That seems to be the content of pretty much every news report he’s featured in. What doesn’t fit this narrative stays on the cutting room floor, allowing him to avoid certain inconvenient facts, including about his very establishment background and current life that demonstrate he’s very far from a man of the people.

Some are so good at playing their characters that they even get invited on entertainment shows as well as the news — Boris Johnson regularly got invited onto Have I Got News For You, not just as a panellist like regular politicians, but as the guest host of the show. That’s a role normally taken by much-loved comedians, and contributed to propping up his assigned reality character ahead of his role in the Brexit vote. In the US, Trump was regularly awarded the same honour on Saturday Night Live.

So it’s little wonder that a star of a reality TV show, like the congress hopeful I met, sees her next career move being into reality news, playing a ‘politician’ character.

The last year has seen the biggest success of that, with the US now gaining a reality TV president. He’s still an executive producer on The Apprentice, even while holding the highest executive position in the government. Again, he knows how to play his role and how to generate emotionally driven storylines for the reality news.

But he’s taken the format further.

In the same way that sometimes the stars of a show bust out of the convention of the format — Miranda breaking the fourth wall of the sitcom to turn and wink at the viewer as if to say “See, it’s all pretend, but aren’t we having fun”—so Trump is breaking the fourth wall of reality news.

“See, it’s all fake news!” he and his team can say as they turn to the cameras to comment on some bad publicity.

And the trouble is, that after the news media has played the reality news game with them for years, how can it defend itself against that accusation?

How can it show that the ‘Bowling Green massacre’, or the ‘Swedish terrorist attack’ are really fake news, and not the reality-style fake news that they’ve been shown to have played along with Trump on for years?

They’ve helped him build this ‘character’ of the ‘man of the people’ and ‘successful businessman’ turned politician that ‘says it how it is’, and ‘fights the establishment’. They’ve run with the storylines he’s given so generously, of things to be angry about or upset about or laugh at. They’ve gratefully run all those minutes of easy airtime and column inches about ‘crooked’ Hillary and fabricated or exaggerated scandals.

But now things are suddenly serious. Things that were fun and ‘reality’ are now real. People’s livelihoods and lives could be destroyed, people could die.

That wasn’t in the original concept for the format, and now the director and producer are in the gallery watching the screens, realising they’ve lost control of the show.

Back in the trendy restaurant in San Diego with the Congress-hopeful, she is about to leave with her friends and has given me her name and told me to look her up online.

“What will I find if I do?” I ask.

“Well there’s my campaign website, that’s where to find out more about me and my campaign,” she pulls the site up on her mobile and shows me. “Apart from that it’s mostly just articles by some journalist on the paper here who hates me. He’s a Democrat and is totally biased, so he tries to make out there’s all these scandals and stuff. Ignore all that, just look at my campaign site.”

I guess she was saying that any unfavourable press coverage was just ‘fake news’. The way she spoke about it was something we’d all hear a lot in the Brexit and presidential campaigns — from Trump, Farage, Boris, May and the other players on reality news.

The two most important roles of the news media in a democracy have always been to provide the electorate with the facts they need to know to make decisions at the ballot box, and to hold power to account for its promises and ethics. But those priorities have now been trumped by the need to be entertaining.

And that’s the fault of us as the audience as much as it’s the fault of the journalists.

However you voted, whether you got the outcomes you wanted or not, and whatever your political colour and shade — we’re all paying the price for our demand for news to entertain.

Steve Parks is a writer based in London, England. Follow him on Twitter and continue the discussion.

Thanks to Joe Baker for review and feedback.